Fall is here, and that means pumpkins and gourds are popping up everywhere—on porches, in centerpieces, and at every farmers’ market. But did you know there’s a native gourd that’s been growing in North America long before the decorative ones hit the scene? Enter the buffalo gourd, a wild cousin to pumpkins and squashes that calls the central and southwestern U.S. home. Known for its rugged look and, well, a bit of a strong smell, this gourd isn’t just a fall decoration—it’s been a part of the landscape for centuries, with a history full of unique uses and ecological importance. Let’s take a closer look at this lesser-known gourd and see why it deserves a little more love this season.

What is the Buffalo Gourd?

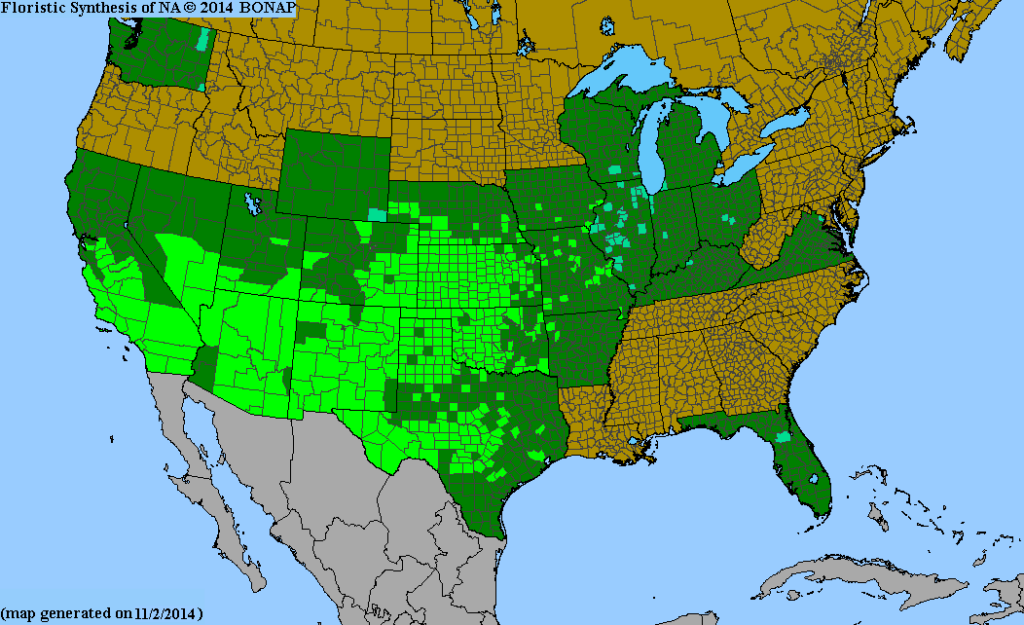

The buffalo gourd, scientifically known as Cucurbita foetidissima, is a malodorous plant native to the central and southwestern United States as well as northern Mexico. Also called stinking gourd, Missouri gourd, wild gourd, and coyote gourd, it is a close relative of cultivated gourds such as pumpkins. The plant is characterized by large, rough, hairy, triangular leaves that can grow up to 12 inches across. Its bell-like yellow flowers are 2-3 inches long. Buffalo gourds produce green-striped fruits that mature into yellow tennis ball-sized gourds, about 4 inches across. As a monoecious plant, it bears both male and female flowers, allowing it to self-fertilize through insect pollination. Like many of our native plants, the buffalo gourd’s story goes far beyond its appearance, and it was used for centuries by Indigenous people.

History and Traditional Uses of Wild Gourds

The buffalo gourd was traditionally used by Indigenous peoples for a variety of purposes, including medicinal, decorative, and practical uses. Medicinally, tea made from the pulverized roots was used to speed up labor, while the roots also served to induce vomiting and as laxatives. Seeds and flowers were ground into powder to reduce swelling, and mashed plants were applied as poultices to treat skin conditions like sores. Buffalo gourds also had decorative uses; the dried gourds were often painted for ornamental purposes. The plant’s tuberous root was used to make soap, and while the young gourds were edible and prepared similarly to squash, the mature fruits were not. The seeds were also consumed as a food source. But how can we today grow this resilient plant in a home garden?

Growing Buffalo Gourd

Buffalo gourds are hardy perennial plants that bloom from June to August and thrive in arid or semi-arid environments, making them ideal for low-water, drought-tolerant gardening. Native to the southwestern U.S., they prefer medium to medium-dry soil and do well in a variety of soil types, including sandy, loamy, clay, or caliche. Buffalo gourds require full to partial sun and grow at a fast rate, though they become dormant during the winter. When growing buffalo gourds from seed, it’s best to soak the seeds in water for 24 hours before sowing them after the last frost. The buffalo gourd is a great addition to the home landscape, but also has an important role in its native environment.

Ecological Role of the Buffalo Gourd

The buffalo gourd plays several important roles in its natural environment. Its seeds serve as a food source for small mammals, while its fibrous parts are used as nesting material by scaled quail (Callipepla squamata). Most notably, the buffalo gourd was once the sole pollen source for squash bees, a group of bees that includes species from the genera Peponapis and Xenoglossa. The most common of these is Peponapis pruinosa. Squash bees are solitary bees, roughly the same size as honeybees, but with a key difference—they carry pollen dry on their hind legs. While the male squash bee spends his mornings flying from flower to flower in search of a mate and often sleeps in the flower by midday, the female remains busy foraging for pollen.

Originally dependent on buffalo gourd for pollen, squash bees have adapted over the last 1,000 years to use the pollen of cultivated Cucurbita plants, such as pumpkins and squashes grown in agriculture. This adaptation is a rare example of how cultivated crops can drive changes in wild pollinators. Squash bees are so effective at pollinating these plants that their work often renders visits from honeybees unnecessary, as they tend to pollinate nearly every available flower. Researchers are now studying squash bees more closely due to their remarkable adaptation and their vital role in agricultural pollination.

Embracing the Native Gourd This Fall

As we enjoy the season of pumpkins, squash, and fall decor, it’s the perfect time to remember the buffalo gourd, a native plant with deep roots in the American landscape. Its resilience, cultural history, and ecological importance make it more than just a quirky wild gourd. Whether you’re decorating your porch or carving jack-o’-lanterns, consider the buffalo gourd’s place in nature and history.

If you live in the Southwest, why not take it a step further? The buffalo gourd is a fantastic drought-tolerant plant that could be a unique addition to your home garden, helping you connect with native flora while creating a sustainable outdoor space. For everyone else, let this fall season be a reminder of how much more there is to discover beyond the gourds we know.

Sources:

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. (n.d.). Cucurbita foetidissima (Buffalo gourd). The University of Texas at Austin.

Moosa Creek Nursery. (n.d.). Cucurbita foetidissima.

Plants for a Future. (n.d.). Cucurbita foetidissima—Buffalo gourd.

Tamminga, M., Diepenbrock, L., Pilling, D., Cameron, R., & Lee, J. (2022). Impacts of climate change on pollinators in North America: Lessons from the 2021 heatwave. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(29), Article e2208116120.

U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Pollinator of the month: Squash bees.