Few voices in conservation have resonated as profoundly across generations as Aldo Leopold’s. As one of the founding figures in modern wildlife ecology and land ethics, Leopold’s timeless reflections continue to shape environmental stewardship. His seminal work, A Sand County Almanac, is more than a book—it is a call to understand, respect, and live in harmony with the land. For those interested in ecology, land restoration, and the preservation of natural spaces, revisiting this classic offers a fresh perspective on the enduring relationship between humanity and nature. This article, originally published in the Jan/Feb 2017 issue of the Wild Ones Journal, celebrates Leopold’s legacy and his ever-relevant message of conservation.

This is an excerpt from the Wild Ones Journal

Current members can log in to read the latest issue or check out the Journal Archives.

By Rick Marsi

It’s that time again: the anniversary of the last time I read Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac. This book never gets old. In fact, if you have a hearth to sit by, with flames you can see as they cast a warm glow on wooden beams overhead, you can read Leopold every winter and not overdose.

That’s because the man knew his outdoor subjects, understood their interactions and described them with love and a literate flair.

It’s also because his conservation message remains compelling. Writing in the 1930s and ’40s (he would die of a heart attack while fighting a brush fire on his neighbor’s land in 1948), Leopold revered his farm in the sand hills of Wisconsin and feared for its future. He described a landscape in flux; a world in which fencerows for pheasants were disappearing as mechanized agriculture promised larger yields and less wasted space. “Clean farming” it was called; Leopold dreaded it. Too often, he wrote, clean farmers live on the land but not by it.

They deplete but don’t replenish. Unless we respect the land, Leopold cautioned, we will destroy it in our lust for progress. To his credit, he realized chickadees can’t vote and that people would have to vote for them. He wrote that wild creatures have the right to proper habitat, to protection from overhunting and commercial exploitation, and to coexist with humankind. We do not own the land, Leopold believed. We are short-term users.

Leopold said this during an era when landfills were called dumps, wetlands were swamps and anyone who spoke against progress because it might mean polluted water was deemed worthy of deportation. Leopold wasn’t deported, but he wasn’t deified either. The fact that more people heed his words today than during his lifetime offers proof of his vision.

An expert in forestry, ecology and game management, Leopold will be remembered for insisting we place aesthetic needs on a par with economic ones. How much is it worth to hear loons cry at night? How much to see condors on the wing in the wild or woodcock on their display grounds? The worth of such things defies estimation. It transcends economics.

Leopold revered deep winter as a time devoid of distractions. He loved to listen when there wasn’t a roof over his head — to a marsh before dawn, to birds and the wind through white pines. He enjoyed being alone in nature, on rainy days and snowstorm days, when others stayed inside. Some days he would rise at 3 a.m. to walk at a time when all were asleep and the land sprawled without boundaries.

Sometimes he would sit on a boulder in the middle of a trout stream and not even fish, just watch. He counted the growth rings on every tree he cut, imagining what the tree looked like as a sapling and what was happening on the land that long ago.

Whenever he harvested a large tree for timber, he silently thanked the landowner before him who had thinned around it and helped it reach up to the sky.

We belong to the land; that was Leopold’s message. What a role model. I look forward to reading his words once again, with bare trees outside and the glow from oak flames warming wooden beams over my head.

RICK MARSI is a naturalist, lecturer, freelance writer and photographer from Vestal, New York. He has received many awards during his career, including an Environmental Achievement Citation from the Federation of New York State Garden Clubs; communications awards from the Upper Susquehanna Coalition and the Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania Conservation District; and the Earth Day Southern Tier’s Earthstar Award for “excellence in promoting public understanding of the natural world.”

Marsi, R. (2017). The Words of Aldo Leopold Never Grow Old. Wild Ones Journal, January/February 30(1).

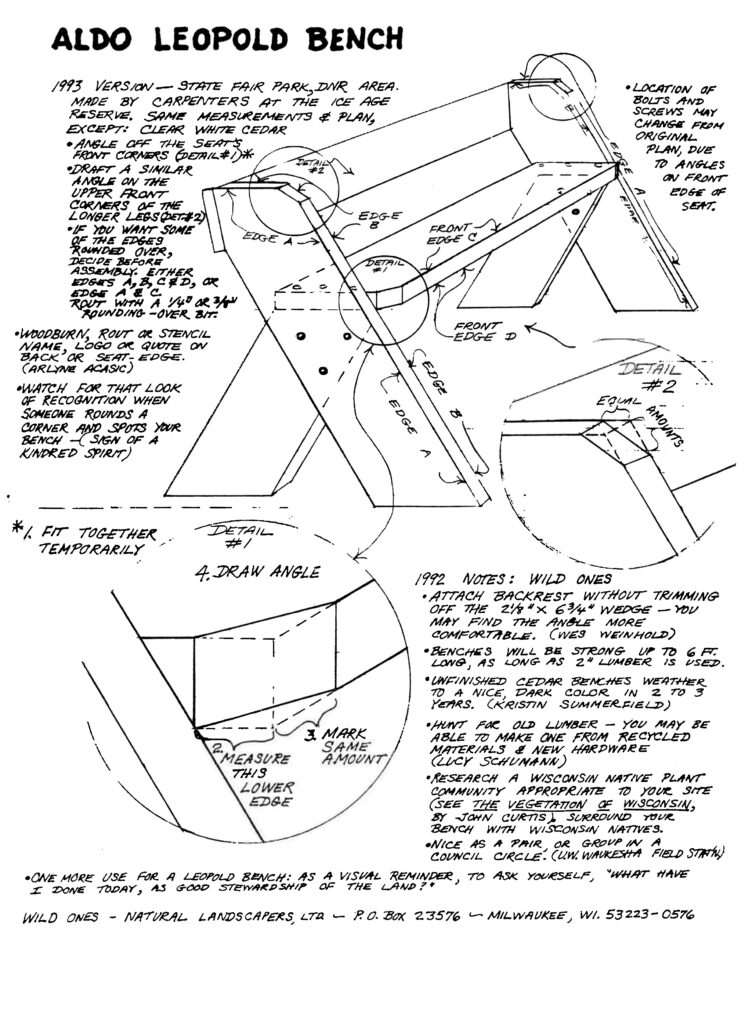

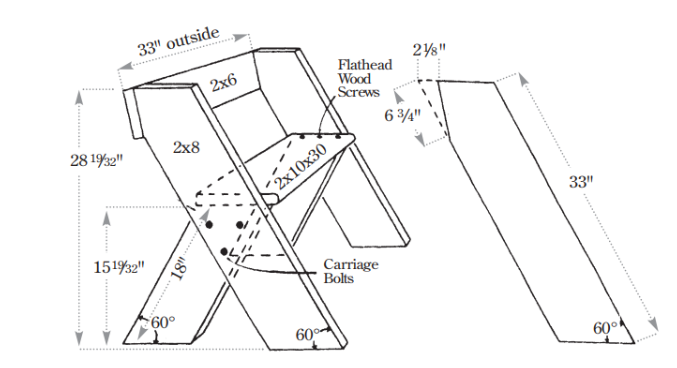

Leopold Bench Plans

Here’s a step-by-step guide to building an Aldo Leopold Bench:

Materials:

- One 2x6x33″ (backrest)

- One 2x10x30″ (seat)

- One 2x8x10′ (legs and supports)

- Six 3/8″x3 1/2″ carriage bolts (with washers and nuts)

- Twelve 3/8″x3 1/2″ flathead wood screws (#12 or #14)

- Optional: Douglas Fir for durability and aesthetic quality

Tools:

- Drill with 3/8″ bit

- Saw (circular or hand saw)

- Measuring tape

- Square

- Wrench (for tightening bolts)

- Sandpaper (optional for smoothing edges)

Instructions:

1. Measure and Cut the Wood:

- Legs (2×8): Cut two 33″ pieces at a 60° angle on both ends. This will form the legs of the bench.

- Seat (2×10): Cut a 30″ piece.

- Backrest (2×6): Cut a 33″ piece at a 60° angle on both ends. This will match the leg angles.

2. Assemble the Legs:

- Position the two 33″ leg pieces to form an “X” shape, ensuring the angles at the top and bottom align properly.

- Mark and drill a hole through the center of the overlapping sections for the carriage bolts.

3. Attach the Seat:

- Place the 30″ seat (2×10) horizontally across the top of the legs. Ensure the seat’s front edge slightly overhangs the legs.

- Drill holes and secure the seat to the legs using carriage bolts. Use washers and nuts to tighten.

4. Attach the Backrest:

- Align the 2×6 backrest vertically with the rear top edge of the seat, angling it slightly backward.

- Drill holes through the legs and attach the backrest using the remaining carriage bolts and screws.

5. Final Assembly:

- Tighten all bolts and screws securely.

- Sand down sharp edges or rough surfaces for a smoother finish (optional).

Notes:

- If you prefer, adjust the size to make a longer bench (up to 48″).

- The bench can weather naturally to a rich, dark color over time, especially if made from cedar or fir.

- Customize the backrest angle for added comfort by trimming the wedge as shown in the diagram.

This Leopold Bench is a simple, functional outdoor seat that reflects Aldo Leopold’s philosophy of practical design and connection to the land. Enjoy building and using it as a symbol of stewardship and craftsmanship.