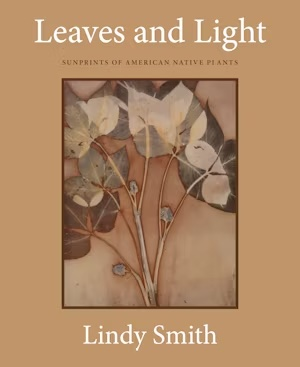

In September 2025, photographer Lindy Smith’s latest book, Leaves and Light: Sunprints of American Native Plants, will hit the shelves. This collection of native plant images uses 19th-century photographic techniques to capture unique images, reminiscent of film negatives but with haunting, unpredictable coloring and shading. Smith worked with native plants from three broad ecological zones — Eastern Woodlands, Prairies and Grasslands, and California — and developed a greater appreciation for the botanical heritage of U.S. landscapes while creating these images. We sat down with Smith to learn more about her process and the artistry behind her new book. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Wild Ones (WO): For those of us unfamiliar with these photographic techniques, what is kallitype?

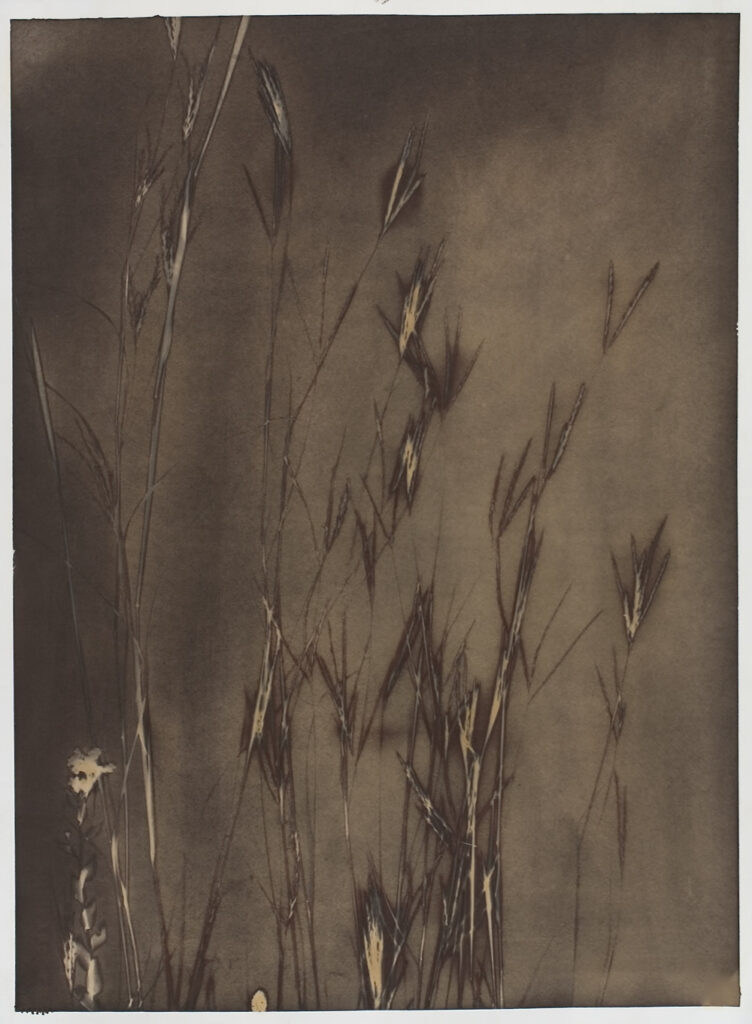

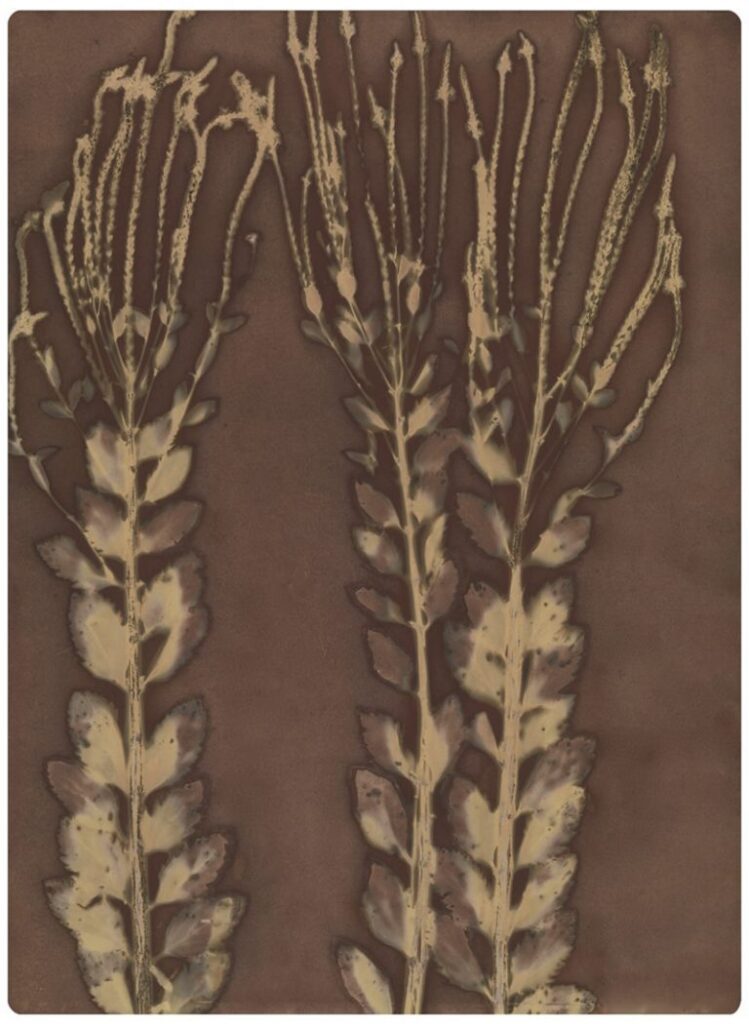

Smith: Kallitype is a process that was patented in the 1880s using iron and silver. I had initially started with a process using platinum, but I realized that kallitype offered a much larger color range than what I’d been using before. In this process, drops of ferric oxalate and silver nitrate are mixed to form a sensitizer and are brushed onto paper, then dried. I collected plants in the wild and worked with them on the paper into a composition of my liking, then sandwiched them between panes of glass for the most contact, and left them under sunlight. Then, the images are developed in a darkroom.

Lindy Smith is an Iowa-based photographer whose work evolved from documenting ranch life to creating sun-printed images of native plants using historic and alternative photographic processes.

WO: Why use these 19th century techniques?

Smith: There was a gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the 1990s that focused on platinum images. I loved the images and purchased a number of them. What drew me to them was the tonal quality and the light; they looked more like paintings than photographs. My background was in documentary photography and this just fascinated me, so I taught myself these processes.

WO: What were you trying to evoke with this style of artwork?

Smith: For me, it was purely about beauty, just highlighting a plant and making something beautiful in a way that people had not seen before. Sometimes curators and gallery owners look at these and ask “What are these?” and they often think they’re paintings. People often don’t realize these had been living plants.

WO: Is it important to have works like these that spur an appreciation of native plants that can then drive greater conservation efforts?

Smith: Absolutely, yes. As I said, at first it was purely about the beauty for me, but it became more about conservation and protection. Now if I were to make this book again, I would be even more careful about what I collected than when I started this project. At one residency in Illinois, I asked permission to collect plants at a preserve, but it wasn’t approved by the right people and that became an issue when I was gathering plants. It’s something Wild Ones readers will understand. And there has been a tremendous amount of growth in interest about native plants. I took a master gardener’s course in 2015 and there was no mention of natives at the time. Now, there are native plant groups all over the Midwest, we have Wild Ones signs in people’s gardens, there is Homegrown National Park, and I started gardening with natives myself about 10 years ago.

WO: Why did you choose these three regions, Eastern Woodlands, Prairies and Grasslands, and California?

Smith: I’ve lived and worked in these regions — I lived in New York State and Massachusetts for 30 years, and Iowa is my home state. I was also in California for a few winters, so they’re the regions I’ve spent the most time in. I started these prints while in New York at a farm I used to live on, then I moved back to Iowa a few years ago. I attended artist residencies in the Midwest, Wyoming and California, and many of those images are part of my book.

Leaves and Light: Sunprints of American Native Plants will be available September 9, 2025, from Prospecta Press. You can learn more about Lindy Smith’s photography at her website: https://lindy-smith-art.com/

WO: Are there other ecosystems you would like to apply a similar treatment to?

Smith: Absolutely, I’d love to do this work in the Southeast and in Appalachia, where there are so many traditional plants.

WO: What was most challenging about this project?

Smith: Physically, it was quite demanding. Handling double sheets of glass that are 2×3 feet, using 6-foot or 8-foot tables with large developing trays — it was taxing. I would pack up my VW wagon with these and all sorts of other materials and drove around the country getting used to new locations, new facilities, things like that. At first I could only see the whole ecosystem. It would take a couple of days to be able to see plants I wanted to make images of among the sea of greens and golds.

WO: Conversely, what was the most rewarding part?

Smith: The rush of seeing an image for the first time when I took it out of the sun. And the developing process, for example, the book’s cover image, I remember the day I made that print and how I felt when it came out of the developer. Seeing how this plant had made this image — that moment is always a thrill.

WO: What’s your next project?

Smith: Well, there were a lot of images to start with for this book, and we trimmed it down so there are still enough images for another book. I’d also be interested in exploring introduced plants, things that people may not realize are non-native or even invasive. I may revisit some of my western work as well.