Victorian England was a comedy of fads and errors. There were parties centered around unwrapping and eating pillaged Egyptian mummies. Taxidermy birds became hat decoration which would pair with a woman’s crinoline, a cage worn underneath the dress to expand it up to six feet wide. And sadly, tonics with radium were drank as a sort of “five hour energy.” Many people attribute the strange quirks and fascinations to the fact that the Victorian era saw most English people experiencing social mobility for the first time in their lives. The industrial revolution was taking place and you could now leave the farm for life in the city which created vast changes to the old social hierarchies. In the United States we have Victorian England to thank for most of our original cultural influences.

Of the more tame fads, the idea that flowers conveyed a type of message became very popular. The term for this is “floriography,” and it found its way into a lot of literature from the time. This fad coincided with the general public’s growing interest in botany as well as the increase in the global plant trade. Foreign flowers like tulips would be used as symbols of passion, or to declare to someone “I love you.” Red roses would be used to tell someone something like “I love you.” The chrysanthemum had become a very popular and captivating flower and had meanings like truth, passion, or “I love you.” (VanDerZanden, 2023) . They didn’t seem to get very creative in England, but the chrysanthemum had a longer history of symbolism in one of its native regions, Japan, where it was an important icon of the imperial office (Laiche, 2023). Back home in the United States, our fascination with the chrysanthemum had been growing substantially. A whole industry had sprung up around things like the “homecoming mum,” another symbol of love for high school homecoming celebrations (Edwards, 2020). Nowadays, plantings or decorative arrangements of the chrysanthemum are common in most states. In any store in the fall you’ll reliably find some mum arrangement, which when planted, displace many of the native fall blooms in our gardens and continue to box out fall natives from the public consciousness. We must consider restoring our native flowers by ending our traditional use of the Chrysanthemum to find new fall blooms for North America.

The chrysanthemum or “mum” for short, is an entire genus of flowering plants in the sunflower family, Asteraceae. The species we’re all familiar with here in the US is Chrysanthemum ×morifolium, a hybrid species that originated in China, naturalized everywhere. The flower is a striking dense artichoke of petals (technically called a pompom) that we’ve seen in every conceivable color. There are other varieties that look much more like simple daisies and asters, and some varieties that have slim quill-like ray petals. In USDA hardiness zone 5-9 they are perennials. Different varieties, of course, have different tolerances.

Arctic Daisy(Chrysanthemum arcticum)

Pyrethrum(Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium)

Daisy(Chrysanthemum majus)

Florist's Daisy(Chrysanthemum ×morifolium)

The idea of a flower that blooms into the late fall seems so special and rare. The mum is in every corporate outdoor fall arrangement and home décor wreath. Potted mums climb the stairs of many a suburban home. It has our full attention in the fall. But if you look beyond the white picket fence, North America has had flowers that bloom in the fall far before anyone brought over the mum from Asia. Besides fall bloom times and a little symbolism, it has rooted itself in the American garden for a few other reasons like color availability and this almost mathematically perfect dome of dense stems and flowers. Let’s see what we can find in North America to meet some of these aesthetics.

New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

So the members of Asteraceae are going to be a no-brainer, and there’s no better than one of the more famous fall genera in the North American prairies. The New England aster (Symphyotrichum Novae-angliae) has an inflorescence with simple cheerful lavender ray petals that present a tidy yellow center disk that, as it matures, ranges from looking like a knitting loom to a koosh ball. It can reach up to six feet tall and, much like a dome of well groomed mums, can form a dense clumps of flower at the top of their thin stems. Unlike the chrysanthemum, asters serve as a larval host for the pearl crescent (Phyciodes tharos), the gorgone checkerspot butterfly (Chlosyne gorgone), and the wavy-lined emerald moth (Synchlora aerata) (Plant database, n.d.).

New England Aster(Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

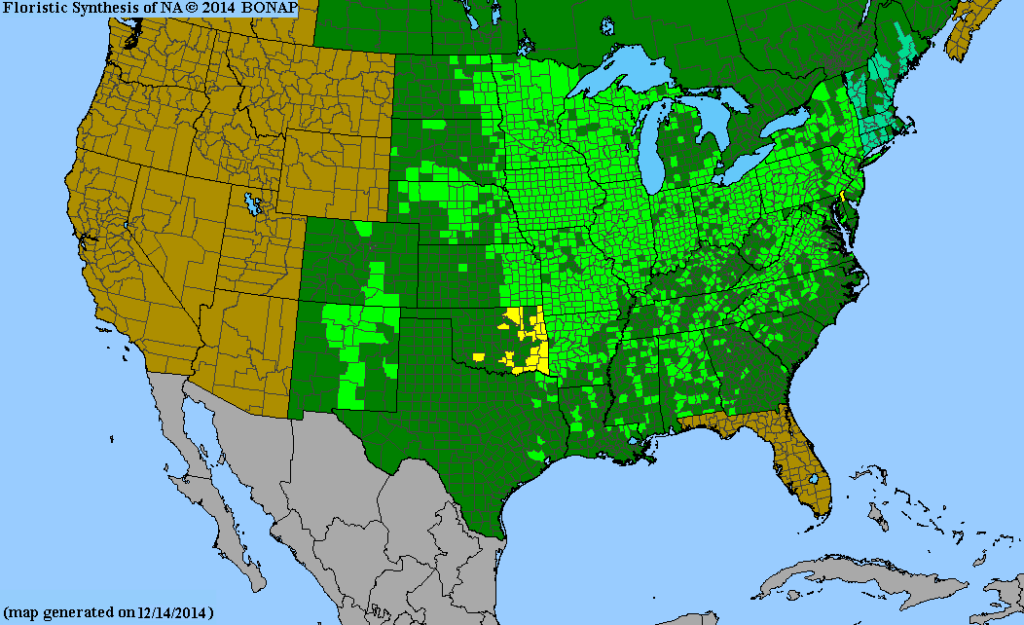

The New England aster has the benefit of an incredibly large native range, despite what it’s Latin species name implies. Though not endemic to California, the flower stretches from Montana to Maine and as far south as Georgia, and it prefers habitats ranging from the partial shading of the woodland’s edge to the sun warmed tall grass prairies. You’ll be pleased to know that this is a broadly accessible species. I have yet to see a native plant seller that didn’t have Novae-angliae. And if you reside in the few states that lie outside of this range, there are other species of Symphyotrichum that will be native. No guarantees on whether the aesthetic of those can rival the mum like Novae-angliae can.

Ox Eye Sunflower (Heliopsis helianthoides)

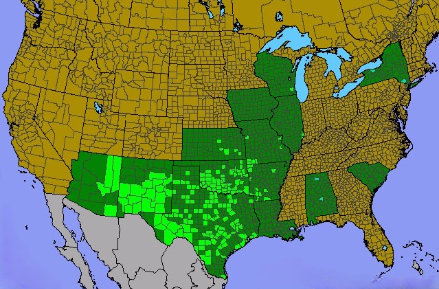

A great majority of the US east of Wyoming hosts the genus Heliopsis which in Greek would basically mean “looks like the sun.” The species then translates to something like “looks like a sunflower.” We have a flower with a bit of an identity crisis. What sets it apart from the true sunflowers is that the brilliant yellow ray petals won’t wither away until dormancy in the winter. The florets are also vastly different. They top a cone receptacle and form a ring of brown to give it an almost eye-like appearance. This has inspired the common name “ox-eye daisy” (not to be confused with Chrysanthemum leucanthemum, a North American invasive).

Smooth Oxeye(Heliopsis helianthoides)

Heliopsis will be widely available and there are plenty of hybrids to choose from if you don’t like the simple daisy look of the wilder variety. It blooms in the late summer and early fall and peters out by September. In this regard, it does fall a month short compared to the Chrysanthemum.

In its feral existence it grows in clumps and flowers singularly and the ray petals are simple and tend to have one to two rows. But we have been able to cultivate many varieties of this species including the example I have shown here called “Asahi,” which bares a much more complex ray petal pattern that comes a lot closer in look to the commonly sighted Chrysanthemum x morifolium. I’m happy to show you such a close resemblance, but it comes with the caveat that deviations from the original wild flower can come with some unknown (and some known) consequences. We know, for example, that purple coneflowers cultivated by humans to have a different ray petal color are no longer recognizable to their host insects (White, A. S. 2016). Changes to the amount of petals alone may not be enough to deter precious pollinators, but it’s worth being cautious. Regardless, even if it is a hybrid, switching your Chrysanthemums to a hybrid native is a great leap in the right direction.

American Basketflower (Centaurea americana)

Okay, hear me out. The modern chrysanthemum has numerous hybrids that really stretch the imagination of how this flower could possibly appear. Some of these varieties called “quill,” “spider,” or “thistle” have incredibly wiry, web-like florets. This can be a great way to have a flower that you are familiar with as far as caring requirements, but be able to have novel and interesting landscaping additions. Centaurea americana, commonly called American starthistle or American basketflower, is a very unique and showy flower native to south-central North America and attracts bees, butterflies, hummingbirds, and surely more. It’s heat tolerant thanks to its native origin, and if you live in the area you should have no issue finding seeds or starts from native local nurseries. Know, though, that there are many other reasons why this species is unlike chrysanthemums. It blooms in the summer and is an annual. The bloom can last as long as August and is known to be pretty easy to grow. Unless heavily manicured, the flowers do not tend to grow in dense clumps, and are more sparse and wiry. This should all be water under the bridge, in my opinion, because look at that flower! It’s incredibly showy and large (4”-5”) on a stem that can reach up to 6’ tall. A firecracker of food for insect species of the Southwest. This gives the great chrysanthemum of Japan a run for its money.

A footnote for those of you interested in finding a similar flower for your region. Centaurea is a genus that hosts a great deal of terrible invasive species in North America. Do your research to avoid some of these potential misidentifications.

Conclusion

The chrysanthemum, or at least the ones we’re familiar with, aren’t invasive. But they’re truly everywhere when it comes to fall-time. If you can’t find them in planters ready for you to place in the ground or decorate the front porch, they are included in wreaths and other home decor. We all have to face the fact that the chrysanthemum isn’t just a flower; it really is part of a language. It doesn’t just mean “I love you,” it now stands for the fall, homecoming, and so much more in other cultures. But we should all consider that it’s a flower best left for those cultures. The famous flowers of floriography are a snapshot of a trend of a very peculiar era in history when people were only just learning about flowers from other countries. It’s only historical coincidence that we in the States ended up obsessed with all of them. North America is host to countless flowers in the fall. Some, like the goldenrod, have finally made it into the pantheon of canonical fall flowers, giving the natives here a voice of their own. It’s been centuries since the Victorian era so we should be able to define our own meanings with the native wildflowers we have here. For one thing, it means restoration and resilience, our ability to revive the biome of North America. And maybe after we’ve built up our native language we can find a new way to say “I love you”.

References

VanDerZanden, A. Last reviewed: January 2023. (2024, August 1). Flowers and their meanings: The language of Flowers. Yard and Garden.

Laiche, I. (2023, August 27). Hanakotoba – the meaning of Japanese flowers. Japan Avenue.

Edwards, B. (2020, July 30). The history of the texas homecoming mum and how the tradition came to be. KPRC.

Plant database. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – The University of Texas at Austin. (n.d.).

White, A. S. (2016). From nursery to nature: evaluating native herbaceous flowering plants versus native cultivars for pollinator habitat restoration. The University of Vermont and State Agricultural College.