She was a mother, a friend, a gardener, and an environmentalist. But for those early Wild Ones members nearly 50 years ago, she was an inspiration.

This is an excerpt from the Wild Ones Journal

Current members can log in to read the latest issue or check out the Journal Archives.

Lorrie Otto, who died in 2010 at age 90, may be best known for her activism, which played a crucial role in Wisconsin being the first state to ban DDT in 1970 and, two years later, in the United States.

But she was also the inspiration for what would become Wild Ones. According to Wild Ones archives, nine people attended a natural landscaping workshop offered by the Schlitz Audubon Center of Milwaukee in 1977 and became interested in the new concept of landscaping with native plants. Their enthusiasm launched the “Wild Ones Garden Club” in 1979, eventually becoming the Wild Ones Milwaukee-North (Wisconsin) Chapter and blossoming into today’s national nonprofit educational organization whose mission is to promote native landscapes through education, advocacy, and collaborative action. Today, Wild Ones has about 100 chapters and 36 seedlings in 36 states, totaling nearly 12,500 members.

The nine founding members relied on Otto as their resident expert, and she took responsibility for programming.

Rochelle Whiteman, who hosted the first Wild Ones membership meeting at her Glendale, Wisconsin home, said her gardening hobby turned into a mission thanks to Otto.

Whiteman, who gave the eulogy at Otto’s funeral, said she didn’t know anything about native plants when she first met Otto. But Otto, in her gentle way, persuaded others to do things for Wild Ones that they never would have done without her influence, she said.

“I loved Lorrie more like a mother,” Whiteman said. “I felt that she raised me to do something. We were just gardeners, but Lorrie taught us to be leaders. But the most wonderful thing happened. It gave me a purpose. I was into gardening before I met her … but she allowed me to spread the philosophy about natives. She told us to pass along the word (about natives) just as she did for us.”

Otto asked Whiteman to speak to small gardening clubs, school groups, men’s groups and educational groups about native plants and how they differ from nonnative species.

She would also send people to Whiteman’s or other members’ homes with little or no advance warning. “Once she sent British photographers to their homes for a TV program about the revolution of landscaping that started in the Midwest,” Whiteman said, adding that she was surprised when, about a year or so later, she heard from a cousin living in Israel that she had just seen Whiteman’s yard on TV.

When some of the members questioned if they had the skills or could do whatever task that was given, Otto always believed in them, Whiteman said. “She collected people who had talents, and she used their talents. I don’t think she could have imagined that Wild Ones could grow as large as it is.”

In fact, she didn’t even imagine it would become a national organization in the beginning, Whiteman said.

Whiteman said Otto often urged people to rescue valuable plants if they saw them being dug up or discarded. “I remember driving by a street that was being widened when I saw a plant, so I stopped and dug it up,” she said. “But as I was digging it up, I was stopped by a police officer who asked what I was doing,” she said. “I told him, ‘I’m doing God’s work.’”

In other words, Otto’s work.

Rae Sweet, a founding Wild Ones member, recalls how Otto would have parties in her backyard to show people native landscaping and tell them how to do it.

“She was just a wonderful woman,” Sweet said. “Lorrie was powerful, quiet and poetic and led by example and storytelling. She always had something to tell us at our early meetings at the Audubon, and she was also in charge of choosing speakers and planning our yearly seminar.”

Lorrie told the garden club members about her childhood walks when she often would discover rare native plants — including one she later found in the ravine behind her home.

“She taught us to follow her on bulldozer alerts and pointed out the natives and how to bring home some of the soil filled with microbes surrounding these plants,” Sweet said. “Years later she sent a Ph.D. student to my home to do her thesis on the very topic, comparing my wild yard microbes to the neighbors’ lawn microbes.”

Sweet recalled that Otto’s home was usually filled with good smells as she liked to cook and bake. “She was this neat, easy-to-talk to person. She’d talk about her daughter, marriage and food. I have Lorrie’s pie crust recipe, and I can’t replicate it even though I’m a baker. Her hands were just the right hands to work the dough.”

Otto often wore a big hat and a square poncho. “She always wanted to look the same so people would recognize her when they saw her,” Sweet recalled. “She was tall, stately with gray hair and just gorgeous.”

Sweet said she met Otto around 1982, when the members who all lived near the Schlitz Audubon Center would meet regularly to talk about plants and tour each other’s properties. In 1985, Otto decided they should redo someone’s yard with natives, billing it as an alternative to traditional landscaping.

“I raised my hand the highest,” Sweet said. So not long after, Otto, Mark Feider, and Margo Fuchs came to her home in the spring. Borrowing water hoses from friends, they laid out paths in her yard and dug out circles of Kentucky bluegrass to convert her front yard to natives.

Since PBS was just getting started in the Milwaukee area, Otto approached the station, which would loan out cameras in hopes of encouraging local programming. “Lorrie created a series of eight to 10 programs for PBS,” Sweet said. “The half-hour programs showed people how to use garden hoses to make paths and plug in native plants…”

Sweet recalled that she would often go to work in the morning and notice one of her native plants had died. But by the time she returned home, Otto had already replaced it.

“She really wanted my yard to be a showplace for people to come and see,” Sweet said. Schlitz Audubon Center also held tours, and Lorrie would hop on the bus and stop by all these different houses. It really developed into a group of people who were following Lorrie.”

Sweet said Otto helped Wild Ones grow by delegating responsibilities. “She became our programming chair because she knew so many people in Milwaukee. She’d write articles for the Wild Ones Journal, then known as the Outside Story, plan trips and constantly tell us things to do. Lorrie was just special to talk to. When she would describe a butterfly flitting around, you just listened. She used her hands to talk, but she was flowery in her speech.”

Otto also liked to tell the story of her fight to get DDT banned, which began when she found a bird dead outside while it was building its nest. “Those were the years when you’d see planes going over low to spray DDT,” she said. “I can still see her telling people how birds were dying because of it… She just wanted to be remembered for wanting the earth to be a better place for people to live, and for people to respect the earth and the land.”

Sweet said going over to Otto’s house was fun. “We’d sit, watch the birds, talk and drink an iced tea,” she said. “She had some type of chicken wire netting that was soft so the birds wouldn’t fly into her windows. It would really bother her to see a bird fly into glass.”

Otto also had a couple of cats that enjoyed watching the birds as well, Sweet recalled.

Carol Chew knew those cats and even adopted one when Otto moved to Bellingham, Washington, to be near her daughter. Now a member of the Wild Ones Nation’s Capital Region (Maryland) Chapter, Chew said her husband, Dan, and Lorrie’s ocicat, Sam, got along well. So well, that Otto was determined Dan was the right person to take care of the cat when she no longer could. In 2018, the cat moved with the Chews to Rock Creek Woods, near Washington, D.C.

Chew said she met Otto in 1987 during one of the first weekends after her family moved from Portland, Oregon, to Milwaukee. “I had been doing native landscaping in 1971 when we bought our first house in Sonoma, California, but I never had anyone to work with. When I arrived in Milwaukee and found out there was a group called Wild Ones, it really filled a need.”

Once she and Dan planted about 90 native species in their yard, Lorrie started bringing people to their home on Wild Ones bus tours. Chew said she fondly recalls seeing Otto’s car regularly pulling into her driveway.

“She was either bringing someone to show them our yard or coming with materials she wanted me to read through,” she said. “I had given her a computer, but she didn’t use it. Everything she did was hand-typed.” Chew became her computer helper, often editing material for her.

Chew said Otto was extremely knowledgeable. “She really delved into studying various species of native plants. She had the kind of personality where she could work with many different people and help them get started on their native landscaping.”

But Otto was also politically engaged, recognizing how laws could impact native landscaping. “We had an ordinary-sized house, but once we had 50 people in our living room with a speaker from the Al Gore campaign because of Lorrie. She was kind but honest and would let someone know if they were overstepping or not contributing. She was passionate about all she was doing.”

Otto also helped people fight for the right to plant and keep natives in cases where city or village ordinances or homeowners’ associations considered them weeds, Chew said, adding that her yard was one that was cited. “Lorrie had to work hard to overcome attitudes, but people liked her infectious laughter and her warm personality.”

Chew said Otto was ahead of her time. “Back in the 1970s and ’80s, it wasn’t easy to find native plants,” she said. But gradually, garden centers began to sell more native plants because of Wild Ones members in the area.

Throughout her life, Otto was humble, Chew said. “I gradually was able to piece together in my mind the story of her earlier work to get DDT banned,” she said. “She had arranged for scientists and researchers to come from a great distance to meet and to stay at various homes. But this was before the internet, so the scientists wanted to stay together at her home to talk about their studies. They’d eventually fall asleep in her living room, and she’d have to tiptoe around them in the morning.”

Paul Ryan remembers Otto telling those stories of scientists and researchers at her home. Ryan met Otto as an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and ended up working for her and taking care of her property for over a decade.

She took dead robins to the city to show them what has happening due to DDT, Ryan said. “The scientists camped out at her house, stayed up late assessing data and had a big pow wow to put it all together.”

Ryan said Otto always encouraged him by being supportive and affirmative. “Almost every time I came over, we’d go inside and sit by her big picture window, and we’d look out on her backyard bird feeders,” she said. “We’d talk about anything; she was an interesting person … and I respected her a lot. She kept me going down the path I started by pointing out the strengths she saw in me.”

When he was young, he did more than just maintain her property. “I’d wash her windows with vinegar and newspaper, and she hired me to dust all her books in her library and exercise the spines. But that also gave me exposure to every book and magazine she owned, including newsletters from the Botanical Club of Wisconsin.

Ryan said Otto could be critical, but not meanly so. “She had experience in things I didn’t have, and I respected that. In the beginning, I didn’t know anything.” But Otto told him stories about how she didn’t know much in the beginning, too.

“Once she saw plants on the side of the road that she liked, so she dug them up, and it was purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria). She quickly learned that was not the right thing to plant,” Ryan said, laughing.

Otto was funny, liked to laugh, and was good-natured. He said, “She was generous with her time and serious about what she was trying to accomplish.”

Otto had lived in her Wisconsin home for 45-50 years, and when she decided to move near her daughter, she knew she had a lot of stuff — unique artwork, rugs, everything she had collected through her lifetime — that she had to get rid of, Ryan said.

“She had some stuff at her daughter’s because she would go there to visit, but she took a few of her belongings with her,” he said. “I drove her to the train; she had a brown paper bag with a few things in it. She told me, ‘I’m wearing two bras and two pairs of underwear so I don’t have to carry so much.’ Everything else was sold or left behind.”

Some parts of Otto’s landscaping still exist on her former 2-acre property. “Parts of it have been reworked, portions have been largely neglected… But things of value are still there.”

Ryan also said that Otto was politically progressive. When she was younger, she spent a lot of time working on projects like berms in her neighborhood, which was one of the first Wild Ones initiatives.

One time she was working on those berms when someone started spraying pesticide and she fell down and passed out.

“She said she remembered lying there and thinking she would die,” he recalled. “But she said she couldn’t because so-and-so was still president, so she couldn’t die today. I can imagine vividly what she’d say” about today’s world.

Bret Rappaport, Wild Ones’ first lifetime member, started working with Otto in the late 1980s when he volunteered with the then Sierra Club Lawyer’s Roundtable. “We got together once a month with a sack lunch and helped people with environmental problems they didn’t know how to solve,” he said. One of the cases revolved around a Chicago resident who was being prosecuted for violating the city’s weed ordinance since she was growing native plants.

He soon heard about a “woman in Milwaukee” who had successfully helped a New Berlin homeowner battle that city’s weed ordinance law and won after bringing in experts who testified that the homeowner’s plants weren’t weeds. So Rappaport reached out to Otto, who then sent him a package of information and gave him much advice.

On behalf of five residents with native landscaping, Rappaport ended up suing the city of Chicago to declare their weed ordinance unconstitutional. “The case got unbelievable press,” he recalled, with national media interviewing him and Otto.

Rappaport said he ultimately lost the Chicago case, but he became known as a national expert on weed laws. In the 1990s, he flew throughout the country giving speeches, often sponsored by native plant societies or municipalities, and writing law review articles, including one put on the Environmental Protection Agency website that gave native plants much-needed legitimacy.

“We lost the battle of litigation, but we won the war,” Rappaport said. “Today, there are fewer weed cases that aren’t actually weeds and people with native plants aren’t being prosecuted for violating weed laws.”

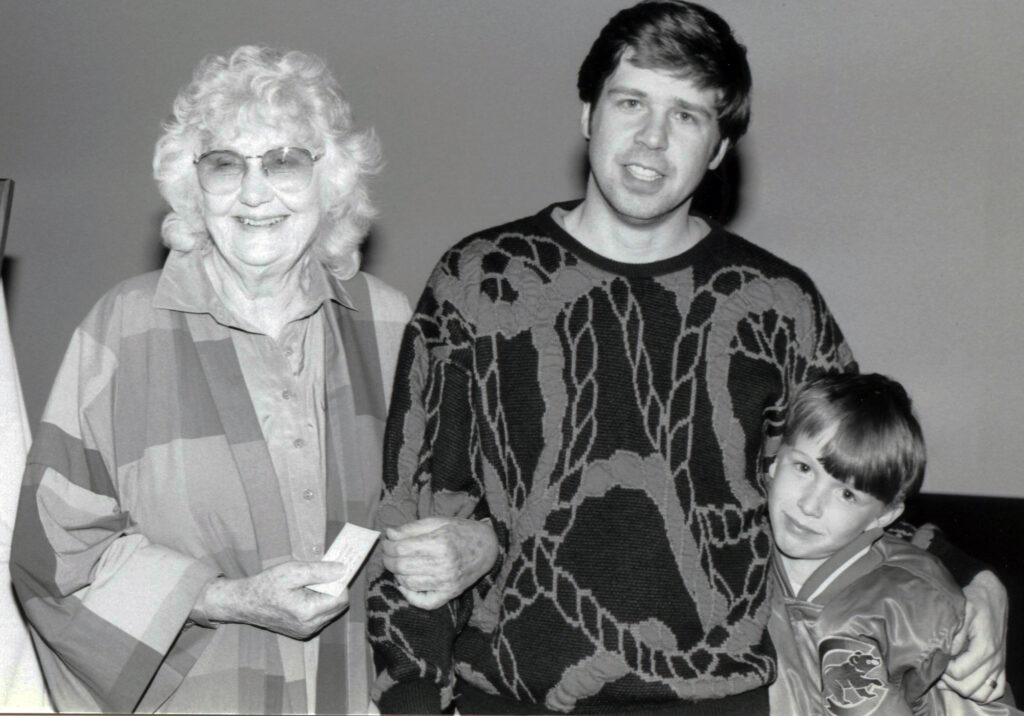

Otto continued introducing Rappaport to other Wild Ones members, and soon he and his wife, Jina, started replacing parts of their lawn with native plants in their 1-acre suburban Illinois yard. As time passed, the Rappaports continued to develop their yard and become more active in Wild Ones. He recalled a visit to Lorrie’s home with Jina and their two sons, Jeremy, then 4, and Conor, then 2, to tour her yard.

“We sat in her house and talked …. but the boys became antsy, so she said, ‘Let’s go walk around the yard,’” Rappaport recalled. “For the next hour or so, the boys followed her around. She even showed them a little bird house that had a mouse living in it.”

The boys were smitten with nature.

“It was a magical day, but what makes it even more special is that the little 4-year-old boy is now secretary on the Wild Ones national Board of Directors,” Rappaport said. “Jeremy went on to earn a degree in wildlife biology, then a master’s degree in restoration ecology, and now is the land manager at Riverside Park in Milwaukee.”

And coincidentally, the main prairie in that park was started by Wild Ones.

Eventually, Otto asked Rappaport to become the national Wild Ones president.

“I told Lorrie I don’t have the experience to run a national organization, that I wouldn’t know what I was doing,” he said. “But Lorrie said: ‘None of us know what we’re doing. We really need your organizational skills.’ She had more faith in me than I had in myself.”

He eventually agreed to take the president’s role and began drawing up bylaws, setting up the structure for the local chapters, creating budgets and more. On June 8, 1990, Wild Ones Natural Landscapers Ltd. was organized under Articles of Incorporation — Non-stock Corporation Law, Chapter 181 of the Wisconsin Statutes. On April 11, 1995, Wild Ones was granted exempt status under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue code for educational purposes.

In hindsight, Lorrie knew that someone with a background in business and law was who was needed at the time.

Rappoport said Otto was humble about her accomplishments. “She felt her role was more of a teacher than of an advocate,” he said. “She focused on one-on-one interactions and whoever she was with at the moment.

“From little acorns, large oak trees grow,” Rappaport said. “That Lorrie’s magic. Her encouragement to others wasn’t like a mentor or cheerleader. It was like a guardian angel.”

Rappaport said Otto was a source of inspiration for many. And despite not being one of the nine original members who started the organization, her guidance helped guide and grow the group.

“Lorrie’s legacy is that preservation and appreciation of our natural world can and should be done on the smallest scale,” Rappaport said. “We think of native and environmental organizations as saving national parks and fighting climate change. But Lorrie taught us we can all do our part, no matter how small the plot of land you own,” he said. “The question becomes what we do with that plot of land. Until I met Lorrie, I didn’t look at my own front yard and realize I could make a difference by … planting a butterfly garden or … leaving dead trees standing as snags. Lorrie opened my eyes to all the possibilities…”

Perhaps one of her best-known quotes was the one printed in her obituary: Otto said: “If suburbia were landscaped with meadows, prairies, thickets or forests, or combinations of these, then the water would sparkle, fish would be good to eat again, birds would sing and human spirits would soar.”

Otto has inspired so many in Wild Ones to soar.

Schmitz, B. A. (2025). “Lorrie Otto: Godmother of Natural Landscaping ” Wild Ones Journal, 38(2).

Help us raise $10,600, enough to fund one full year of Seeds for Education grants.

Join Us in Remembering Lorrie on Her 106th Birthday

Lorrie Otto never set out to create a national movement. She set out to care for her place, to protect the birds and plants she loved, and to teach others to do the same.

Today, nearly 50 years later, her spark has grown into a national network of Wild Ones chapters and a youth education program that keeps sowing seeds for future generations.

By celebrating her 106th birthday with a gift, you’re not just remembering her. You’re living her legacy.