With drastic declines in insect pollinator populations, gardeners have heard the call and are doing the work to help build better, wildlife-friendly landscapes. Efforts are growing with more and more platforms providing information on how to plant gardens for pollinators.

This is an excerpt from the Wild Ones Journal

Current members can log in to read the latest issue or check out the Journal Archives.

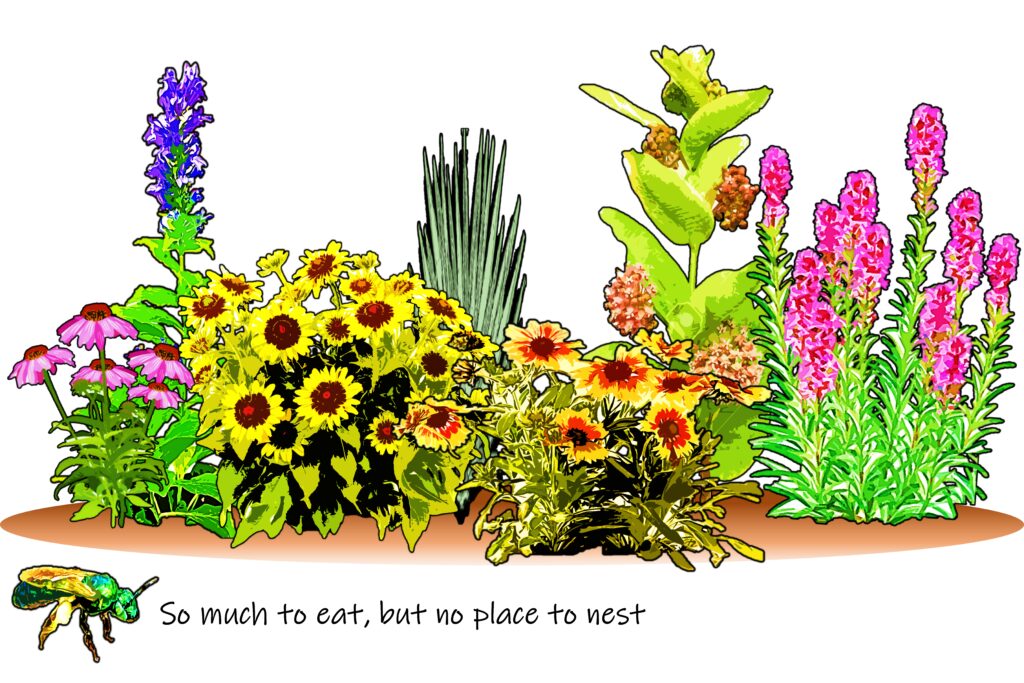

Extension offices and local environmental groups often create native flower plant lists, and every so often there are even informational tidbits about creating bee hotels or watering areas. These informational articles are extremely helpful, but they tend to leave folks thinking about pollinator habitats as an isolated plant community.

As with most topics, the simple ideas are only a summary of complex, nuanced realities. Scientists are still learning about the incredibly elaborate systems that are pollinator habitats. One of the very clear things the data tell us is that pollinator habitats are more than just plants.

In this article, I provide information on how to contextualize a pollinator garden within the ecosystem. Following that section, I explain different non-plant resources, as well as ways to recreate those resources.

Contextualizing pollinator habitat

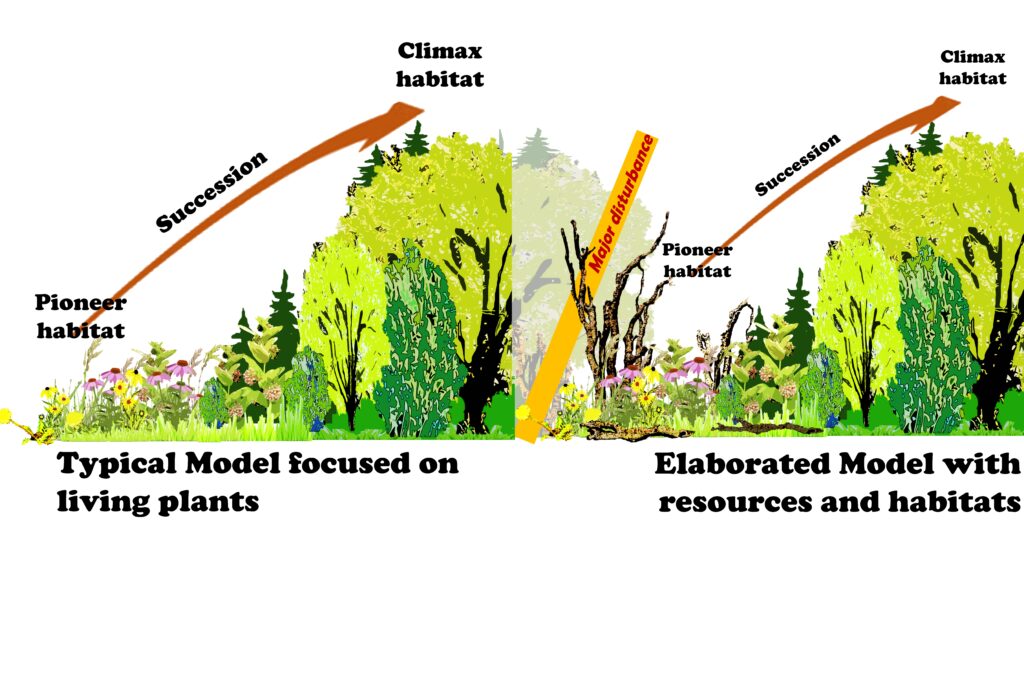

Before we get too far into the details of creating robust pollinator habitats, it is important to understand the natural cycles that these habitats evolved with, and should experience in, native landscapes and ecosystems. When we consider that the majority of plants included in pollinator plant lists grow in full sun, we can assume the natural plant community that we are emulating is supposed to be meadow or grassland, so this article will focus on those habitats. Most people are taught that meadow or grassland habitats are “pioneer habitat,” which can be true, but in many ecoregions and especially those in the Great Plains and Arid Southwest, these habitats are also “climax communities.”

Furthermore, the typical model of succession that is taught in biology courses tends to give us the idea that these early successional plant communities exist only as plants on barren landscapes. This is the same problem we see with the plant lists for pollinator gardens.

However, for about two-thirds of the ecoregions in the United States, meadows and grasslands form where a disturbance kills off trees. In a more holistic model, in the Great Plains and various savannah plant communities, disturbances like fire and annual grazing from bison, elk, pronghorn and deer facilitated the grassland plant communities and kept woody plants away. All these disturbances have been removed from our gardens, so it is important to recreate the resources and nutrient cycles in our pollinator habitats to keep them healthy.

For every region, the ecological disturbances that create and maintain meadows and grasslands will be different. However, the ways a gardener can identify the ecological disturbances and the resources that would be created is the same, everywhere. First, identify the different plant communities that exist in the ecoregion. If large trees would grow in any of those plant communities, dead wood is going to be an important resource for pollinators and other wildlife. If the garden is in an ecoregion where large woody plants are rare, then dead wood is less important, at least above ground.

Underground plant structures are important as well. This includes the woody root systems of oaks, as well as dense underground stems and roots of plant species in regions without forests or wooded areas. As these non-living woody structures break down, both above and below ground, microhabitats are created where species will nest, overwinter and take refuge. Incorporating woody materials into gardens can be simple or complex and can easily make a garden more beautiful.

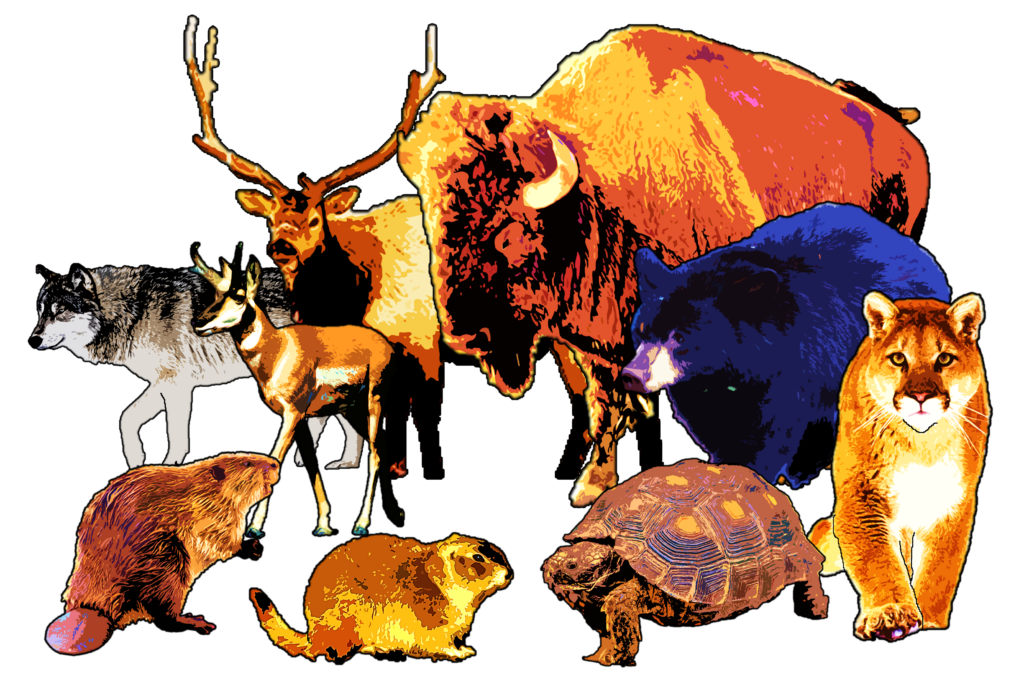

Similarly, it is important to consider which animals are historically native to the region, especially those called ecosystem engineers. This includes animals that create burrows like prairie dogs, gophers, tortoises and ground squirrels; disturb plants and soils like large herbivores; beavers that create wetland networks and can kill forested stands; and predators, pathogens and other pressures that affect populations and nutrient cycles. Unfortunately, the actions of previous generations have drastically altered the ranges of many of these habitat-altering animals, so it might be most helpful to visit a local natural history museum or simply use the internet to discover which ecosystem engineers are native to your location.

There are also important species that have not had their ranges drastically reduced, but that are eradicated from urban environments, like groundhogs, gophers and coyotes. However, the wildlife that depend on the structures and disturbances these ecosystem engineers create are often desirable. For example, most landowners and gardeners do not appreciate large burrowing animals digging new holes or killing plants, but many folks are excited when toads, box turtles or bumblebees – all of which need burrows but do not create them – find a home on their property. In many situations, recreating burrows, clearings and even wetlands can be done in such a way that it improves the habitat of the garden and makes a beautiful feature.

The third ecological aspect to consider for creating a robust pollinator habitat is the geology and soil structure of the natural landscape. This includes exposed rocks, floodplains and natural hydrological cycles like ponding, sand deposits, overall soil types and different slopes. In most areas, especially urban communities, soils are heavily modified and graded. In the wild, however, those soils are important for overwintering wildlife, soil nesting bees and a variety of other animals to carry out their life cycle. By simply recreating one or two of these areas in a garden, pollinator diversity and local abundance can improve dramatically.

Adding non-plant resources

Woody materials: Many gardeners already add aspects of naturally occurring woody resources like bird boxes and bee hotels without realizing what they are imitating. In natural meadows and grasslands, large dead trees would have hollow sections for birds to nest in and numerous small holes caused by wood boring insects that bees use for their nests. There are many “bee hotels” available for purchase, but most are bad for bees. A good bee hotel should have tunnels or tubes that are six to 12 inches deep, easily cleaned or replaced every two years, and not contain “butterfly houses” or slits, which usually attract predators and not butterflies.

Adding natural wood structures to gardens can be as simple as adding a log that is at least 6 inches in diameter by 12 inches long, either standing up or laying down. Logs are easily tucked into plant beds for plants to grow over or they can be used as borders and pedestals. More complex installations are also possible, including intricate log borders or focal features that use large, branched trunks to plant around. Tree companies will sometimes deliver these if you contact them. Tree species with thick bark will be used by pupating moths and butterflies as the bark peels away. Wood boring insects will create tunnels in the main wood and cavity nesting bees will eventually use those tunnels. Similarly, drilling a few holes into the log with a 5/16-inch drill bit will create nesting sites for bees. To recreate underground woody resources, dig a hole at least 12 inches wide and deep, then fill with untreated mulch (leaves and twigs work, too) and pack it down. This can be done under the log, or a stone shelter to save space. The underground, decomposing mulch mimics decomposing root systems and will be used by overwintering toads, bees and other insects.

Soils: Gardeners often only think of soils as they pertain to plants, but just like plants, many species of wildlife need soils with specific characteristics. For example, many birds need dry, silty areas to take dust baths; butterflies need nutrient rich, wet soils to “puddle” or consume nutrients; and ground nesting bees will only nest in specific soils. There are more than 2,500 ground nesting native bees in North America and less than 500 species have their nests described, so it is difficult to create nesting areas for all the local species. However, most native bee nests that have been described use sandy to clay soils and rarely use heavy loam soils.

To encourage native bee nesting, excavate an area a minimum of 12 inches wide and deep in a dry, sunny location. Amend the soil with small grain sand, like paver sand, to about 50% to 80% of sand and fill the excavated area. Adding different features to the top will appeal to some species over others. Features to add include a spattering of pebbles, large stones either flat on top or semi-covered, sprawling plants or nearby bunch grasses. These areas can be integrated in multiple locations across the landscape, including rarely used areas like by HVAC units, back corners or fence lines. The more soil diversity an area can have, including slope and sun-exposure, the more you will increase the nesting opportunities for native bees.

Rocks and crevices: Both soil-nesting and cavity-nesting bees can benefit from the addition of larger rocks in a garden, as well as many other species of wildlife like lizards, frogs and toads. If the area you live in has localized rock outcroppings, there are likely pollinators that use those resources. In places with geologic formations made of thin layers or rocks that readily crack, stacking wide, flat rocks in a sturdy design will create crevices for cavity nesting bees, as well as shelter for lizards, pupating insects and other wildlife. Similarly, installing rocks over a loose, sandy soil can create nesting sites for soil nesting bees that prefer to use the soil/rock interface.

By adding just one of the above resources to a pollinator habitat, local populations can be boosted. There are also a variety of resources specific to ecoregions not discussed here. For more information on projects and wildlife habitats, check out videos and presentations on YouTube, habitat-focused books, and the resources local pollinators or conservation groups have put together.

By Shaun McCoshum

Shaun McCoshum, Ph.D., is a conservation ecologist with expertise in pollinator and plant communities. His published works include scientific articles, video presentations, wildlife gardening books, and a variety of informational pieces.

McCoshum, S. (2023). Pollinator gardens – going beyond the plant lists to create a robust habitat. Wild Ones Journal, 36(1). p. 26-28.

For those looking to take their efforts a step further, consider participating in the Wild Ones Certified Native Habitat program. This program offers a structured way to ensure your garden meets the essential criteria for supporting local wildlife. By certifying your habitat, you join a community of gardeners dedicated to ecological restoration and conservation. Certification not only validates your hard work but also helps raise awareness and inspires others to contribute to the preservation of native ecosystems.